The Sandy

MISSION OF THE BASIN: Collaborate with nonprofits, agencies, and businesses to augment the recovery of endangered species.

In Oregon’s shady Sandy River basin, native populations of salmon and steelhead were listed under the Endangered Species Act in 1998. In 2006, over a dozen groups, including The Freshwater Trust, formed the Sandy River Basin Partners. Together, the Partners developed and executed one of the first comprehensive and science-driven plans for restoring the basin. The Partners used a hierarchical approach to prioritize more than 100 opportunities for conservation and restoration projects, which are now nearly complete.

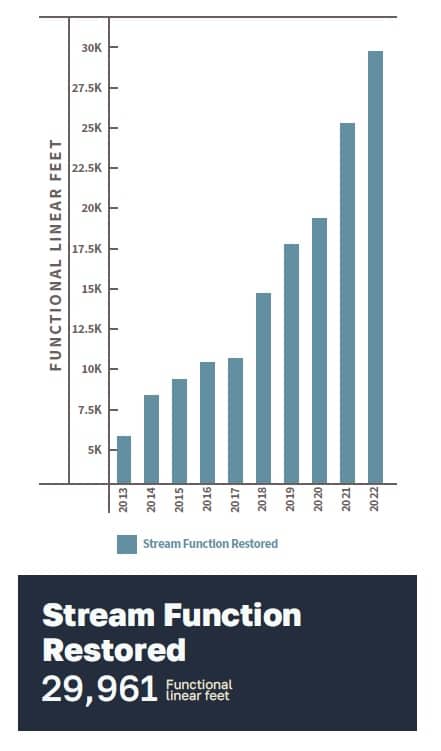

To date, 26 side channels have been restored on the Salmon River, 300 large wood structures have been installed and more than 58,000 feet of historic side channel have been reactivated. Close monitoring by the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife shows there has been a more than 320% increase in adult coho in the Salmon River between 2010 and 2021. The number of Chinook returning to spawn in the lower Salmon River is more than 150% of the long-term average and the number of steelhead spawning increased 300%. The number of juvenile fish reared in the restored side channels of Still Creek and Salmon River has also increased — double for coho and 8–10 times for steelhead. In 2018, TFT accomplished a big milestone in the basin, completing all originally scoped restoration actions for Still Creek, setting it on a trajectory for full recovery.

With documented fish response, the $12.5 million in work completed to-date in the Sandy has become a roadmap for successful basin-scale restoration that can be replicated in watersheds across the West.