The Upper Willamette

MISSION OF THE BASIN: Collaboratively work with stakeholders to improve water quality and streamside forests.

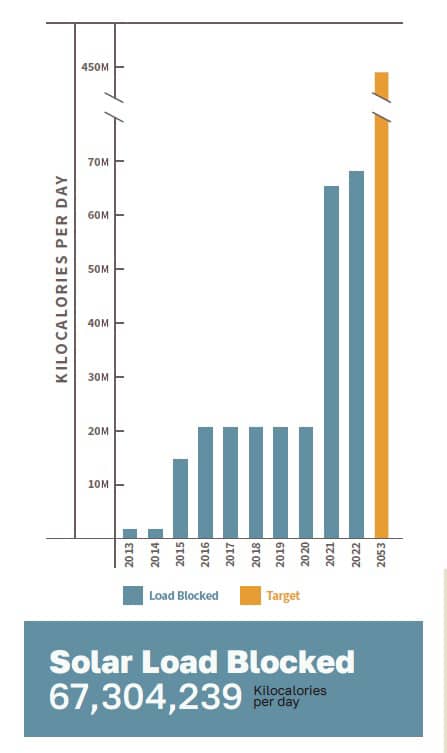

The rich blue waters of the McKenzie River quietly flow through western Oregon toward the Willamette Valley. Since 2012, the Metropolitan Wastewater Management Commission and The Freshwater Trust have partnered to restore streamside forests along this river and its tributaries. We recently expanded the program to restoration along the Middle Fork Willamette and Coast Fork Willamette. This water quality trading program plants native trees and shrubs along streambanks to help the utility comply with its wastewater permit under the Clean Water Act. As the plants grow at each restored site, their shade blocks solar load (sunlight), which generates credits for the utility and helps keep the stream cool for native fish. The plants also filter sediment and excess nutrients from reaching the stream and improve terrestrial habitat.

After five pilot projects, the full program received regulatory approval and new planting sites throughout the Upper Willamette basin are underway in 2023. TFT manages the credits the program generates that keep the MWMC in compliance, while on-the-ground implementation is led by local watershed councils and other restoration practitioners. Together, this coalition works to ensure that restoration plantings are put in the right place to complement the efforts of adjacent restoration and conservation programs for maximum uplift. In this way, the watershed benefits from local expertise and more of the funding stays in the community. Once implementation is complete in 2027, this program will be the largest water quality trading program that TFT has executed, with shade plantings at as many as 30 sites. This approach — combining TFT’s knowledge of process, analytics and program-building with the place-based expertise of local partners — demonstrates a viable method to scale up and fix more rivers faster.