The dollars and sense of restoration

An operator deftly maneuvers a compact skid steer along the edge of Little Butte Creek in southern Oregon. His target is the 10-foot tall stands of invasive Himalayan and Armenian blackberry bushes that choke the streambank. By the end of the day, he’ll have mowed and mulched more than five acres, along with the help of crews wielding chainsaws, to clear the noxious weeds from the site.

A team of river engineers and restoration project managers supervise the movement of 25- to 40-foot logs as they’re strategically piled and anchored to the streambank. The wood juts out over the creek, and one engineer jumps into waist-deep cold water to shove a branch into place.

A small team carrying saplings stoops to dig holes and plant native red-osier dogwood and black cottonwood. By the end of the summer, teams like this will have planted two miles of streamside trees to prevent erosion and improve native fish habitat.

Crews remove invasive vegetation to prepare a streamside site for restoration.

What is the common denominator here? All these people are part of the “restoration economy.” And Oregon is one of the best places for it.

Generally speaking, the restoration economy is comprised of the economic activities and jobs that contribute to restoring the environment and creating ecological benefit. A 2015 study shows that “ecological restoration is a $9.5 billion industry, employing about 126,000 people directly” in the United States. Additionally, “the restoration economy indirectly generates $15 billion and 95,000 jobs, bringing restoration’s total economic output value to nearly $25 billion.”

Like the examples above, the jobs created by the restoration economy are local, skilled and provide fair compensation.

“It’s a slow and steady drip into the local economy,” said Denis Reich, Southern Oregon program director for The Freshwater Trust (TFT).

Since 2012, TFT has been managing restoration projects along southern Oregon’s Rogue River and its tributaries, such as Little Butte and Bear Creeks. The projects are part of programs that help the City of Medford manage impacts of warm-water discharge and the Bureau of Reclamation manage requirements under a biological opinion for restoring cold-water fish habitat.

For projects specifically executed for the Bureau of Reclamation in 2016, TFT’s contractors and sub-contractors totaled 54 people from local businesses in Jackson County and surrounding areas. That’s the equivalent of 1,200 hours for services such as archeology surveys, wood harvesting and hauling, site preparation and construction, fence building, well digging, irrigation system set up, and tree planting and maintenance.

Dollar-wise, the projects that TFT and its partners implemented in 2016 on behalf of Reclamation penciled out to $1.7 million for large wood structures and $655,000 for native re-vegetation.

Those are not small numbers, especially when infused into economies that once thrived on now shrinking industries, such as logging and mining.

“I’ve hired contractors who sometimes work managing forests for timber production. Now they are doing work geared toward forest health more often, and I send them out to clear invasive blackberries along creeks,” said Lance Wyss, restoration project manager for TFT. “They have a great skillset we can use for our restoration projects.”

Wyss also notes that owners of streamside property who once mined their land for gravel are now interested in restoring these sites.

“We can recruit some of these streamside properties into our riparian programs. The landowners get paid to lease the land to us to rebuild it, rather than extract from it,” he said.

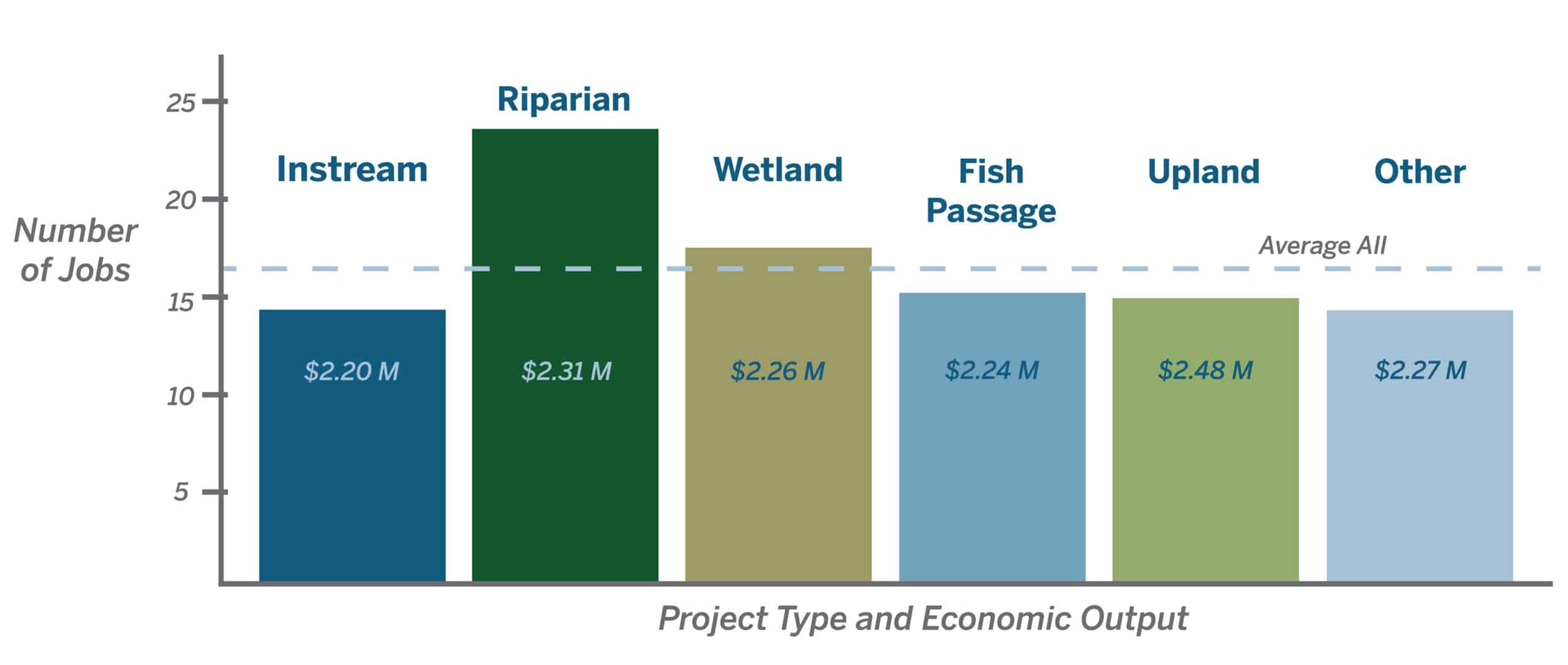

Research by Max Nielsen-Pincus and Cassandra Moseley shows that between 16 and 23 local jobs are supported in Oregon for every $1 million spent on restoration. Riparian, or streamside, restoration projects, which tend to involve labor-intensive planting and fencing, supported the most jobs and wages, represented in the figure below.

Landowners participating in one of TFT’s programs in the Rogue are financially compensated for allowing the revegetation activities on their land, which provides them with a steady income for 20 years. And, while the Nielsen-Pincus study reported that 60% of spending on restoration projects happened in the county where the work occurred,

TFT has found that the local contractors, suppliers, staff and restoration professionals involved in its program are actually receiving 75% of those restoration dollars.

Furthermore, every public dollar spent in Oregon for restoration results in an additional 1.4 to 2.4 times the amount of economic activity.

“There’s plenty of restoration work to go around in southern Oregon,” said Reich. “However, there’s always the challenge of finding enough funding for it.”

To meet that challenge, TFT has used a combination of both direct-project funding from agencies and municipalities along with grant funding from foundations and agencies.

A team begins the careful placement of large wood for fish habitat.

When the funding is there, contractors like Todd Marthoski, owner of M&M Services, are ready. He’s spent time moving earth for irrigation trenches, pipelines and gas tanks. But he’d prefer the precision-machinery work such as installing large wood structures that create habitat instream for juvenile fish.

“The economic benefit to our community is huge, while adding essential ecological benefits to our rivers and streams,” said Marthoski.

June 28, 2017“Working in the restoration economy is a win-win. It feels rewarding to finish restoration projects that enhance natural resources.”

#Bureau of Reclamation #restoration economy #river restoration #Rogue River #Rogue River Basin

Enjoying Streamside?

This is a space of insight and commentary on how people, business, data and technology shape and impact the world of water. Subscribe and stay up-to-date.

Subscribe- Year in Review: 2023 Highlights

By Ben Wyatt - Report: Leveraging Analytics & Funding for Restoration

By Joe Whitworth - Report: Transparency & Transformational Change

By Joe Whitworth - On-the-Ground Action – Made Possible By You

By Haley Walker - A Report Representing Momentum

By Joe Whitworth