50 years of the Wild & Scenic Rivers Act reveals we’ve got work to do

1968’s groundbreaking legislation to protect rivers was a good start but falls short of what’s needed

Joe Whitworth is author of QUANTIFIED: Redefining Conservation for the Next Economy (Island Press), a patented inventor, and President of The Freshwater Trust. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

The free-flowing whitewater of the Rogue River will get your attention fast, and with my first rapid in 1998, I immediately knew why 90 miles had been protected by Congress. On October 2, 1968, in response to an era of frenzied dam development, Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Wild & Scenic Rivers Act to “preserve certain rivers with outstanding natural, cultural, and recreational values in a free-flowing condition for the enjoyment of present and future generations.” This effectively gave the force of law to these values as counterweight to the cost-benefit analyses that had invariably favored damming river systems for irrigation (in the West) or flood control (in the East). The Act signaled the end of an era, and hinted at the beginning of a new one.

A collection of movie stars, authors, and sports heroes who vacationed there helped put the Rogue among the first eight rivers designated under the Act. And today, the thousands who paddle, fish, sleep next to, and hike alongside this river every year tell the story of its beauty and significance still 50 years later — but only part of the story.

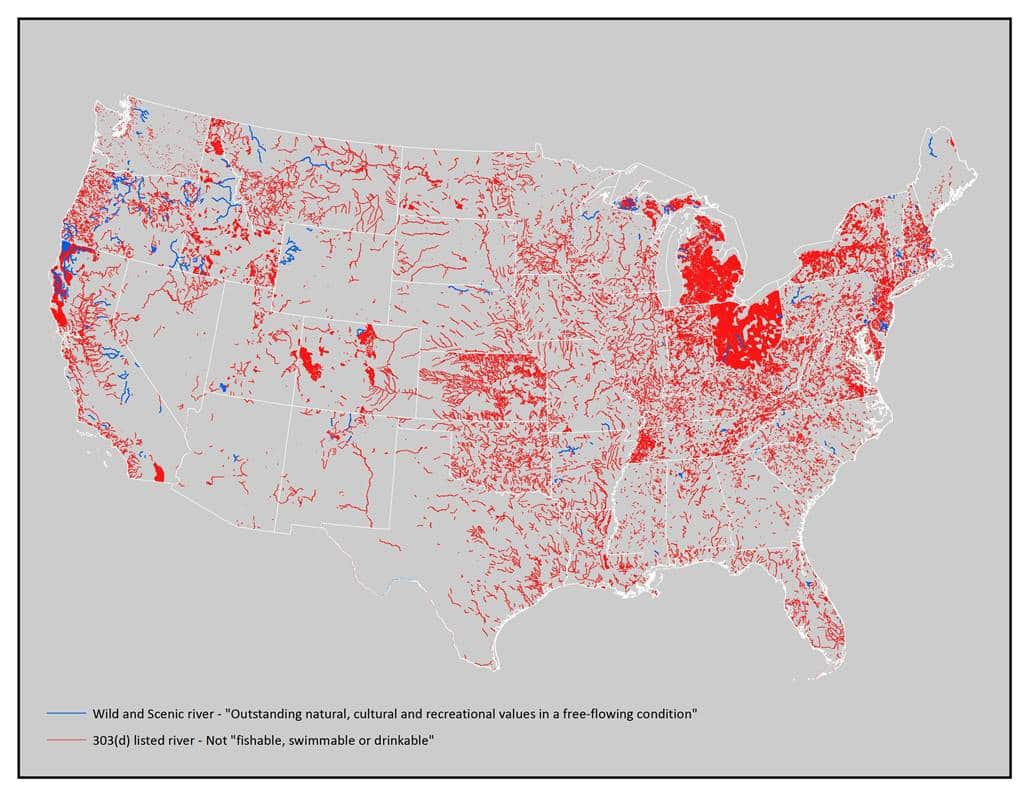

In 40 of our 50 states, nearly 13,000 miles across 203 rivers are deemed “Wild & Scenic” and thus protected from dams and certain development. But what these and the many adjacent miles are not immune from are problems that hinder water quality, such as upstream contamination, irrigation withdrawals, nutrient-heavy runoff and lost fish habitat.

Today, 173 of the 203 rivers that have “Wild & Scenic” sections also have sections designated as impaired under the Clean Water Act — unable to meet its fishable, swimmable, drinkable standard. A full one fourth of the actual wild & scenic miles are impaired.

Like so much of our country’s environmental legislation, noble words are written on paper with no effective through-line to ensure results on the ground. Leading up to the 50th anniversary of the Act, many organizations have called for thousands more miles to be designated over the next half century. This misses the point, because as the last five decades have shown, calling more miles “Wild and Scenic” does not automatically give us healthier river systems.

Having put it to work for the economy without much regard for the downstream effects, the Rogue suffers from excessive water temperatures, sediments and nutrients. Unlike a giant concrete dam stretching bank to bank, the less visible issues go unaddressed. And while the Act stops select “bad” things from happening to rivers, simply holding the line won’t truly preserve these systems — much less improve function, restore native vegetation, prevent erosion, or restore habitat.

There is no product on Earth made by any human that does not require water. There is no human that does not require water. Truly, the health of our waters will determine the prosperity of our lives. And we have grown stagnant. We need prioritized, priced, actionable, and dynamic restoration programs to make these miles great again — achieving health now and resilience for the long-term at a reasonable cost. Leveraging remote sensing, data, and local workforce to fix rivers on the ground, we in Oregon are redefining how the economy and the environment combine to make tangible gains and this can now scale across watersheds nationwide. There have always been those who scream we must choose between natural resource health and a growing economy; between doing right by our environment and putting people to work. In this era of smart technologies, smart policies and smart investments, this is a false choice. Let’s get past the prologue and get on with solving big problems.

Like so many things in 1968, the Wild & Scenic Rivers Act changed the course of our history and of conservation. It was a good start and protected sections of our country’s greatest rivers from events that would have changed them forever. We should celebrate that, while also acknowledging that words on paper alone do not get it done. Let’s resolve to make these waters “Wild, Scenic, and Functional”, and then truly act on those words.

Interested in republishing this article? Contact Haley Walker at haley@thefreshwatertrust.org.

October 2, 2018#policy

Enjoying Streamside?

This is a space of insight and commentary on how people, business, data and technology shape and impact the world of water. Subscribe and stay up-to-date.

Subscribe- Year in Review: 2023 Highlights

By Ben Wyatt - Report: Leveraging Analytics & Funding for Restoration

By Joe Whitworth - Report: Transparency & Transformational Change

By Joe Whitworth - On-the-Ground Action – Made Possible By You

By Haley Walker - A Report Representing Momentum

By Joe Whitworth