A 16,000% increase in fish. Really.

There are worse ways to spend a day than in a dry suit and snorkel, counting fish.

It’s part of the job for some Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) employees.

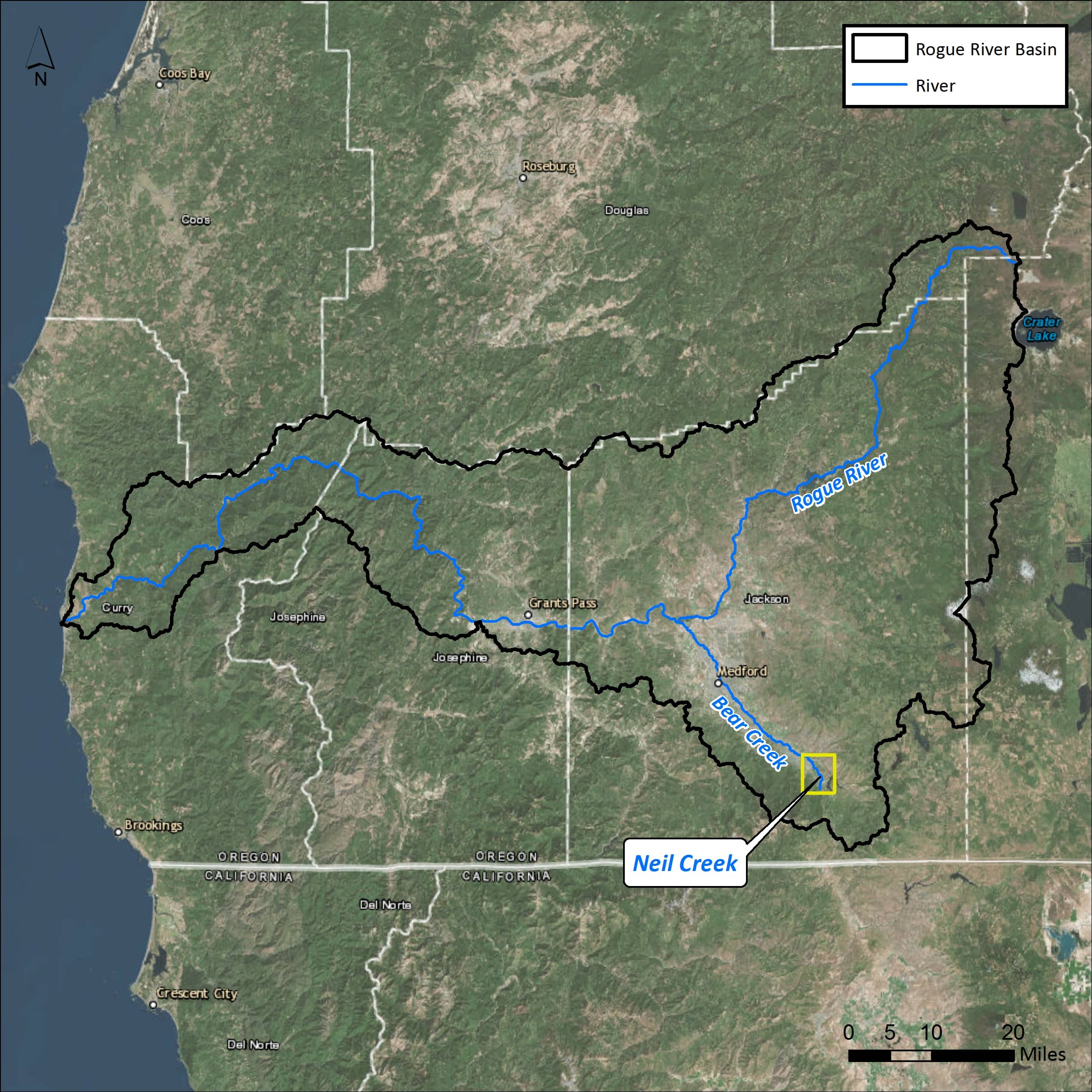

Fish surveys have taken place every year since 1998 in western Oregon. The department tracks the number of fish they spot year after year, providing valuable data about habitat available and water quality. This past year, data was collected in more than 60 places in the Rogue Basin. One of them was a reach of Neil Creek, a snowmelt fed tributary of Bear Creek.

The part of the creek surveyed by ODFW happens to overlap with a mile-long stretch where The Freshwater Trust (TFT) has planted native vegetation, installed dozens of large wood structures, and fenced out livestock since 2015.

“We knew about what this creek could become long before we started work here,” said Eugene Wier, Ashland-based habitat restoration project manager for TFT. “It’s one of the coldest in the watershed, and it has a low gradient that’s perfect for rearing. It’s just the right place for coho and steelhead.”

But its potential to be a fish refuge had long been marred.

Invasive weeds choked banks, which meant there wasn’t adequate shade and native plants couldn’t thrive. There was a dearth in large wood, which helps create the refuge and complexity fish need to spawn and rear. Livestock had access to the water, causing an offload of nutrients and sediment, smothering redds and interfering with juvenile feeding.

Knowing this, TFT began a conversation with the Healy Family, owners of the Historic Dunn Ranch on the outskirts of Ashland.

“The ranch runs along Neil Creek, and it has some of the oldest water rights in the state,” said Wier. “We knew opening the doors to collaborate with a private landowner such as this could yield big results for fish. It’s the same way we get the vast majority of our projects done here in the Rogue.”

In early August, when ODFW employees masked up and dove in as they have for the past 15 years in this location, they validated Wier’s prediction of big results.

Fish counts had jumped more than 16,000 percent after $1.5 million spent, 14 acres of native vegetation planted, over 2 miles of livestock fence built, a network of off-channel livestock watering troughs established, and 47 large wood structures installed.

One juvenile coho was counted more than a decade before restoration began. This year, there were 169. And nearly 80 chinook were spotted when not one had ever been recorded.

“It’s a remarkable return and reinforces the operating thesis of The Freshwater Trust’s restoration,” said Wier. “When we identify the locations best suited to sustain native fish and we invest there, we see meaningful results.”

But scientists don’t rest on laurels after one test.

“Consistency is important,” said Ron Constable, project leader with ODFW. “This is a good sign, but I’ll be more excited if we see numbers like this in future years. Generally though, I’ll admit that this was a pretty good year to stick your face in the water and see some fish.”

TFT works year-round to make connections with new landowners in the basin and open doors for more restoration projects.

“Encouraging stories like these only help us present a compelling case to more people,” said Wier. “There are many landowners that have property where restoration and stewardship could mean the recovery of the native fish in this basin.”

This project was made possible with funding from the Bureau of Reclamation as part of their efforts to recover endangered coho salmon in the inland Rogue.

September 13, 2017

#fish habitat #river restoration #Rogue River #Rogue River Basin

Enjoying Streamside?

This is a space of insight and commentary on how people, business, data and technology shape and impact the world of water. Subscribe and stay up-to-date.

Subscribe- Year in Review: 2023 Highlights

By Ben Wyatt - Report: Leveraging Analytics & Funding for Restoration

By Joe Whitworth - Report: Transparency & Transformational Change

By Joe Whitworth - On-the-Ground Action – Made Possible By You

By Haley Walker - A Report Representing Momentum

By Joe Whitworth